Orson Welles Saw A Major Disadvantage To Making Films In Color

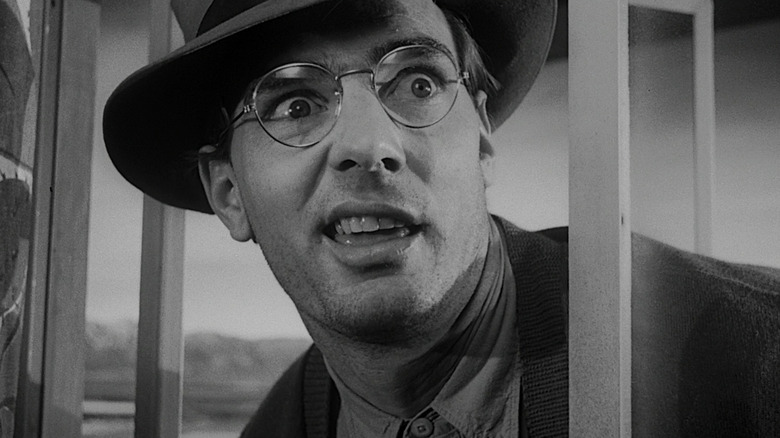

Orson Welles had a knack for beautiful compositions. Sure, his career might've been filled with turbulence, but even a quick glance through the action-director's filmography illustrates just how skilled he was behind the camera. In fact, he even topped our list of the best filmmakers who never won an Academy Award for directing (though he did snag an Oscar for co-writing "Citizen Kane").

Welles was also famously in favor of shooting films in black-and-white rather than color. This surely led to much of his films' visual strength: The stylistic choice cut down on unnecessary color clashes, which in turn led to striking, visually unified images. That high-contrast look is also a big part of why black-and-white films are still made to this day.

Yet Welles' personal rationale for avoiding color film was relatively unusual, even if it undoubtedly showed respect for his fellow actors. As the multi-hyphenate explained to Peter Bogdanovich during a series of conversations spanning multiple years (as collected in the 1992 book "This is Orson Welles"), he felt that color films often ended up undermining actors' performances, stating, "[F]aces in color tend to look like meat — veal, beef, baloney." By sticking to black-and-white film, Welles could keep viewers from feeling unnerved by the distorted skin tones, allowing them to instead focus on the performances at hand.

Color film had major limitations

Now, the deli comparison might've been uncalled for, but Orson Welles had a point. Color film was not always kind to actors, especially in the era when Welles was most prolific. For reference, the director's career spanned from the early '40s to the '70s, though he arguably made most of his best works prior to the mid '50s. During this period, Technicolor's color-film reigned supreme.

Unfortunately, while Technicolor might've had a catchy slogan ("Technicolor is natural color"), a quick glance at your favorite '40s movie proves just how dubious the claim was. Generally speaking, Technicolor films were incredibly saturated and appeared brighter than real life. This hyper vivid look had its uses ("The Wizard of Oz" dialed up its saturation even further, which helped the eponymous fantasy world feel a little more magical), but the bright colors didn't always lend themselves to realism.

Of course, as color movies became increasingly common, other companies tried to cash in on Technicolor's success. Kodak's Eastman Color film — which was used to shoot "Rebel Without a Cause," "2001: A Space Odyssey," and "A Clockwork Orange" — led the pack (via Live About). Still, this development didn't improve the film industry's skin tone accuracy: Eastman Color was almost as saturated as Technicolor.

To make matters worse, Kodak had a long history of ignoring non-white skin tones when creating their film stocks. As a result, Eastman Color heavily distorted many actors of color's appearances. In time, color film would become more accurate, but it took a long time to do so. Until then, the increasingly unpopular black-and-white film created less jarring representations of actors' skin tones.

Welles would eventually experiment (albeit reluctantly)

To give credit where credit is due, Orson Welles would eventually venture outside his comfort zone. His last fictional feature, "The Immortal Story," was shot in color (as were a couple of his unfinished films). In a stroke of irony, the film itself was produced in celebration of France's transition to color television (via Deep Focus). However, Welles wasn't quite so enthusiastic about the film's use of color, nor was he proud of his on-screen performance within it.

When Peter Bogdanovich complimented Welles for his performance as the film's merchant during their conversations, the latter wasn't having it, either:

"It sure in hell wasn't great. I think every really great performance that's ever happened in movies — up to now, anyway — has been in black-and-white."

Welles' venture into color film might seem surprising given his insistence upon black-and-white film looking better, but it was hardly his most shocking experiment. Just days before his passing, he provided the voice for the villainous Unicron in "The Transformers: The Movie." Welles wasn't fond of the role, but his willingness to try new things was nevertheless admirable.

Still, there was one line that Welles never wanted to cross (and justifiably so). Ted Turner, who famously released colorized versions of black-and-white films, had set his sights on giving "Citizen Kane" the same treatment. When Welles learned about these plans, he insisted fellow filmmaker Henry Jaglom not "let Ted Turner deface my movie with his crayons."